Nix is a purely functional package manager. This means that it treats packages like values in purely functional programming languages such as Haskell — they are built by functions that don’t have side-effects, and they never change after they have been built. Nix stores packages in the Nix store, usually the directory /nix/store, where each package has its own unique subdirectory such as

/nix/store/b6gvzjyb2pg0kjfwrjmg1vfhh54ad73z-firefox-33.1/

where b6gvzjyb2pg0… is a unique identifier for the package that captures all its dependencies (it’s a cryptographic hash of the package’s build dependency graph). This enables many powerful features.

You can have multiple versions or variants of a package installed at the same time. This is especially important when different applications have dependencies on different versions of the same package — it prevents the “DLL hell”. Because of the hashing scheme, different versions of a package end up in different paths in the Nix store, so they don’t interfere with each other.

An important consequence is that operations like upgrading or uninstalling an application cannot break other applications, since these operations never “destructively” update or delete files that are used by other packages.

Nix helps you make sure that package dependency specifications are complete. In general, when you’re making a package for a package management system like RPM, you have to specify for each package what its dependencies are, but there are no guarantees that this specification is complete. If you forget a dependency, then the component will build and work correctly on your machine if you have the dependency installed, but not on the end user's machine if it's not there.

Since Nix on the other hand doesn’t install packages in “global” locations like /usr/bin but in package-specific directories, the risk of incomplete dependencies is greatly reduced. This is because tools such as compilers don’t search in per-packages directories such as /nix/store/5lbfaxb722zp…-openssl-0.9.8d/include, so if a package builds correctly on your system, this is because you specified the dependency explicitly.

Runtime dependencies are found by scanning binaries for the hash parts of Nix store paths (such as r8vvq9kq…). This may sound risky, but it works extremely well.

Starting at version 0.11, Nix has multi-user support. This means that non-privileged users can securely install software. Each user can have a different profile, a set of packages in the Nix store that appear in the user’s PATH. If a user installs a package that another user has already installed previously, the package won’t be built or downloaded a second time. At the same time, it is not possible for one user to inject a Trojan horse into a package that might be used by another user.

Since package management operations never overwrite packages in the Nix store but just add new versions in different paths, they are atomic. So during a package upgrade, there is no time window in which the package has some files from the old version and some files from the new version — which would be bad because a program might well crash if it’s started during that period.

And since packages aren’t overwritten, the old versions are still there after an upgrade. This means that you can roll back to the old version:

$ nix-env --upgrade some-packages $ nix-env --rollback

When you uninstall a package like this…

$ nix-env --uninstall firefox

the package isn’t deleted from the system right away (after all, you might want to do a rollback, or it might be in the profiles of other users). Instead, unused packages can be deleted safely by running the garbage collector:

$ nix-collect-garbage

This deletes all packages that aren’t in use by any user profile or by a currently running program.

Packages are built from Nix expressions, which is a simple functional language. A Nix expression describes everything that goes into a package build action (a “derivation”): other packages, sources, the build script, environment variables for the build script, etc. Nix tries very hard to ensure that Nix expressions are deterministic: building a Nix expression twice should yield the same result.

Because it’s a functional language, it’s easy to support building variants of a package: turn the Nix expression into a function and call it any number of times with the appropriate arguments. Due to the hashing scheme, variants don’t conflict with each other in the Nix store.

Nix expressions generally describe how to build a package from source, so an installation action like

$ nix-env --install firefox

could cause quite a bit of build activity, as not only Firefox but also all its dependencies (all the way up to the C library and the compiler) would have to built, at least if they are not already in the Nix store. This is a source deployment model. For most users, building from source is not very pleasant as it takes far too long. However, Nix can automatically skip building from source and instead use a binary cache, a web server that provides pre-built binaries. For instance, when asked to build /nix/store/b6gvzjyb2pg0…-firefox-33.1 from source, Nix would first check if the file http://cache.nixos.org/b6gvzjyb2pg0….narinfo exists, and if so, fetch the pre-built binary referenced from there; otherwise, it would fall back to building from source.

We provide a large set of Nix expressions containing thousands of existing Unix packages, the Nix Packages collection (Nixpkgs).

Nix is extremely useful for developers as it makes it easy to automatically set up the build environment for a package. Given a Nix expression that describes the dependencies of your package, the command nix-shell will build or download those dependencies if they’re not already in your Nix store, and then start a Bash shell in which all necessary environment variables (such as compiler search paths) are set.

For example, the following command gets all dependencies of the Pan newsreader, as described by its Nix expression:

$ nix-shell '<nixpkgs>' -A pan

You’re then dropped into a shell where you can edit, build and test the package:

[nix-shell]$ tar xf $src [nix-shell]$ cd pan-* [nix-shell]$ ./configure [nix-shell]$ make [nix-shell]$ ./pan/gui/pan

Since Nix packages are reproducible and have complete dependency specifications, Nix makes an excellent basis for a continuous build system.

Nix runs on Linux and macOS.

NixOS is a Linux distribution based on Nix. It uses Nix not just for package management but also to manage the system configuration (e.g., to build configuration files in /etc). This means, among other things, that it is easy to roll back the entire configuration of the system to an earlier state. Also, users can install software without root privileges. Read more…

Nix is released under the terms of the GNU LGPLv2.1 or (at your option) any later version.

NixOS is a GNU/Linux distribution that aims to improve the state of the art in system configuration management. In existing distributions, actions such as upgrades are dangerous: upgrading a package can cause other packages to break, upgrading an entire system is much less reliable than reinstalling from scratch, you can’t safely test what the results of a configuration change will be, you cannot easily undo changes to the system, and so on. We want to change that. NixOS has many innovative features:

In NixOS, the entire operating system — the kernel, applications, system packages, configuration files, and so on — is built by the Nix package manager from a description in a purely functional build language. The fact that it’s purely functional essentially means that building a new configuration cannot overwrite previous configurations. Most of the other features follow from this.

You configure a NixOS system by writing a specification of the functionality that you want on your machine in /etc/nixos/configuration.nix. For instance, here is a minimal configuration of a machine running an SSH daemon:

{

boot.loader.grub.device = "/dev/sda";

fileSystems."/".device = "/dev/sda1";

services.sshd.enable = true;

}

After changing /etc/nixos/configuration.nix, you realise the configuration by running this command:

$ nixos-rebuild switch

This command does everything necessary to make the configuration happen, including downloading and compiling OpenSSH, generating the configuration files for the SSH server, and so on.

Another advantage of purely functional package management is that nixos-rebuild switch will always produce the same result, regardless of what packages or configuration files you already had on your system. Thus, upgrading a system is as reliable as reinstalling from scratch.

NixOS has a transactional approach to configuration management: configuration changes such as upgrades are atomic. This means that if the upgrade to a new configuration is interrupted — say, the power fails half-way through — the system will still be in a consistent state: it will either boot in the old or the new configuration. In most other systems, you’ll end up in an inconsistent state, and your machine may not even boot anymore.

Because the files of a new configuration don’t overwrite old ones, you can (atomically) roll back to a previous configuration. For instance, if after a nixos-rebuild switch you discover that you don’t like the new configuration, you can just go back:

$ nixos-rebuild switch --rollback

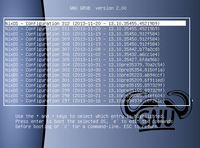

In fact, all old system configurations automatically show up in the Grub boot menu. So if the new configuration crashes or doesn’t boot properly, you can just roll back by selecting an older configuration in the Grub boot menu. Rollbacks are very fast: it doesn’t involve lots of files having to be restored from copies.

NixOS’ declarative configuration model makes it easy to reproduce a system configuration on another machine (for instance, to test a change in a test environment before doing it on the production server). You just copy the configuration.nix file to the target NixOS machine and run nixos-rebuild switch. This will give you the same configuration (kernel, applications, system services, and so on) except for ‘mutable state’ (such as the stuff that lives in /var).

NixOS makes it safe to test potentially dangerous changes to the system, because you can always roll back. (Unless you screw up the boot loader, that is…) For instance, whether the change is as simple as enabling a system service, or as large as rebuilding the entire system with a new version of Glibc, you can test it by doing:

$ nixos-rebuild test

This builds and activates the new configuration, but doesn’t make it the boot default. Thus, rebooting the system will take you back to the previous, known-good configuration.

An even nicer way to test changes is the following:

$ nixos-rebuild build-vm $ ./result/bin/run-*-vm

This builds and starts a virtual machine that contains the new system configuration (i.e. a clone of the configuration of the host machine, with any changes that you made to configuration.nix). The VM doesn’t share any data with the host, so you can safely experiment inside the VM. The build-vm command is very efficient (it doesn’t require a disk image for the VM to be created), so it’s a very effective way to test changes.

The Nix build language used by NixOS specifies how to build packages from source. This makes it easy to adapt the system — just edit any of the ‘Nix expressions’ for NixOS or Nixpkgs in /etc/nixos, and run nixos-rebuild. However, building from source is also slow. Therefore Nix automatically downloads pre-built binaries from nixos.org if they are available. This gives the flexibility of a source-based package management model with the efficiency of a binary model.

The Nix package manager ensures that the running system is ‘consistent’ with the logical specification of the system, meaning that it will rebuild all packages that need to be rebuilt. For instance, if you change the kernel, Nix will ensure that external kernel modules such as the NVIDIA driver will be rebuilt as well — so you never run into an X server that mysteriously fails to start after a kernel security upgrade. And if you update the OpenSSL library, Nix ensures that all packages in the system use the new version, even packages that statically link against OpenSSL.

On NixOS, you do not need to be root to install software. In addition to the system-wide ‘profile’ (set of installed packages), all user have their own profile in which they can install packages. Nix allows multiple versions of a package to coexist, so different users can have different versions of the same package installed in their respective profiles. If two users install the same version of a package, only one copy will be built or downloaded, and Nix’s security model ensures that this is secure. Users cannot install setuid binaries.

NixOS is based on Nix, a purely functional package management system. Nix stores all packages in isolation from each other under paths such as

/nix/store/5rnfzla9kcx4mj5zdc7nlnv8na1najvg-firefox-3.5.4/

The string 5rnf... is a cryptographic hash of all input used to build the package. Packages are never overwritten after they have been built; instead, if you change the build description of a package (its ‘Nix expression’), it’s rebuilt and installed in a different path in /nix/store so it doesn’t interfere with the old version. NixOS extends this by using Nix not only to build packages, but also things like configuration files. For instance, the configuration of the SSH daemon is also built from a Nix expression and stored under a path like

/nix/store/s2sjbl85xnrc18rl4fhn56irkxqxyk4p-sshd_config

By building entire system configurations from a Nix expression, NixOS ensures that such configurations don’t overwrite each other, can be rolled back, and so on.

A big implication of the way that Nix/NixOS stores packages is that there is no /bin, /sbin, /lib, /usr, and so on. Instead all packages are kept in /nix/store. (The only exception is a symlink /bin/sh to Bash in the Nix store.) Not using ‘global’ directories such as /bin is what allows multiple versions of a package to coexist. Nix does have a /etc to keep system-wide configuration files, but most files in that directory are symlinks to generated files in /nix/store.

NixOS is available for download. Since NixOS is a relatively young Linux distribution, you may find that certain things that you need are missing (e.g., certain packages or support for specific hardware), so you may need to add those yourself. Here are some highlights of what NixOS currently provides:

NixOS is free software, released under a permissive MIT/X11 license.